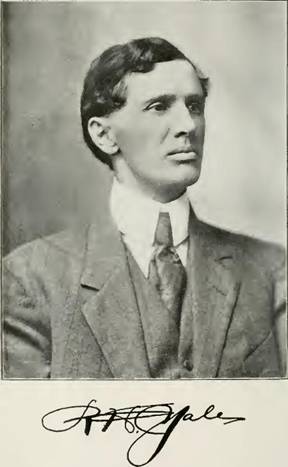

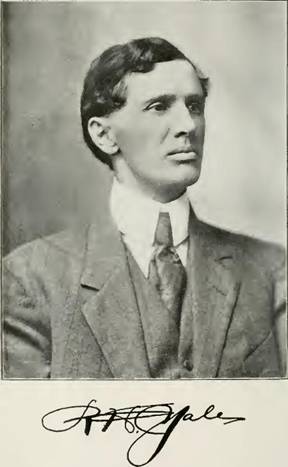

(RODNEY HORACE

YALE.)

(RODNEY HORACE

YALE.)

![]()

![]() Tt? trill

Tt? trill

![]() WAkA\6,`," di„

WAkA\6,`," di„

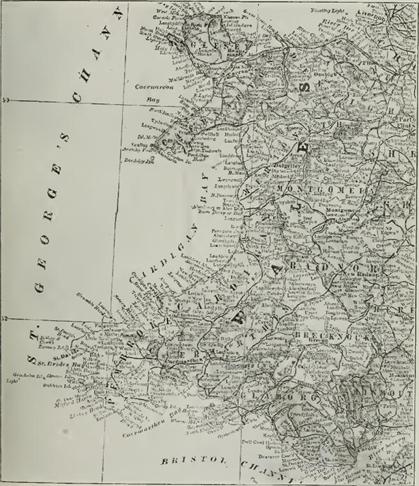

MAP OF

ANCIENT WALES.

MAP

OF MODERN WALES.

![]()

![]() CONTENTS.

CONTENTS.

|

Preface---------------------- Introduction---------------------- Wales------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

Pages 3-5 ------------------------- 7-9 10 1 1-14 |

|

History of Wales (The British Kings and Princes)----------------------- |

15 -53 |

|

Owen Glyndwr

(Glendower) |

---------------------- 53-71 |

|

Genealogy of the

Ancient Yales_ |

72-81 |

|

Biography of

Maurice Fitz Gerald |

74-75 |

|

The Yales of Plas-yn-Yale -------------- |

81-82 |

|

The House of de Montgomery ------------------------------------------------ |

82-84 |

|

Arms and Crests |

84-86 |

|

The Yales of Plas Grono------------------------------------------------------- |

86-95 |

|

The Yales of America----------------------------------------------------------- |

96-591 |

|

Biography of Governor Elihu Yale --------------------- |

------------------ 101-122 |

|

Biography of Linus

Yale, Sr., |

_ _294-296 |

|

Biography of Linus Yale, Jr.,------------------------------------------------- |

437-442 |

|

War Records ----------------------------------------------- |

591-596 |

![]() KEY.

KEY.

A person is only

given one number and it is used as the family heading of the person, as well as

in numbering this person as offspring of the parents. This is the

"Key" to the work. For example Thomas Yale No. 44, page 126, was son of Thomas

Yale No. 29, page 123. All family and children numbers are in numerical order,

so any number can be located at once. Records of persons received late or

overlooked, have been numbered with the letter "A" preceding.

![]()

![]() ILLUSTRATIONS.

ILLUSTRATIONS.

The Author Frontispiece

Coat of Arms I

Map

of Modem Wales--------------------------------------------------------------

II

Map

of Ancient Wales-------------------------------------------------------------

Ill

Llangollen and Dinas

Bran 16

Castle

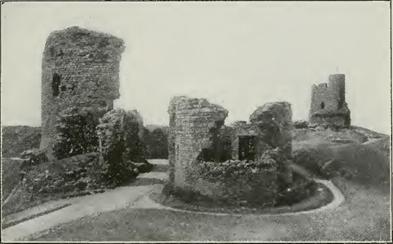

Dinas Bran (Two Views)------------------------------------------------

32

Valle

Crucis Abbey----------------------------------------------------------------

36

Pembroke

Castle--------------------------------------------------------------------

44

Carew

Castle ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 48

Glyndwr's

Mount-------------------------------------------------------------------

52

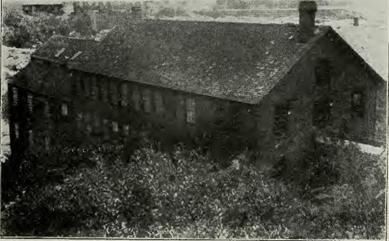

Sycherth

or Cynllaeth-------------------------------------------------------------

60

Nannau (Two

Views)-------------------------------------------------------------

64

Harlech

Castle ------------------------------------------------------------------- __

68

Aberystwith Castle 76 Plas yn

Yale 80 Views at Plas yn Yale 84 Bryneglwys Church 92

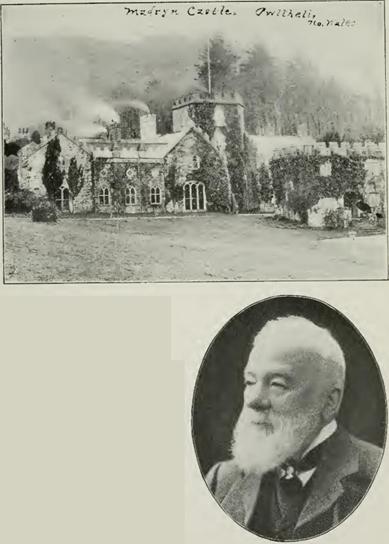

Madryn Castle and Wm. Corbet Yale-----------------------------------------

96

Yale Monument (Oswestry) --------------------------------------------------- 100

Erddig Hall

------------------------------------------------------------------------ 108

Signature of Dr. David Yale---------------------------------------------------- 108

Bishop George Lloyd's House-------------------------------------------------- 112

Gov. Elihu Yale _ .. ------------------------------------------------------------ 116

Gov. Elihu Yale's Letter--------------------------------------------------------- 124

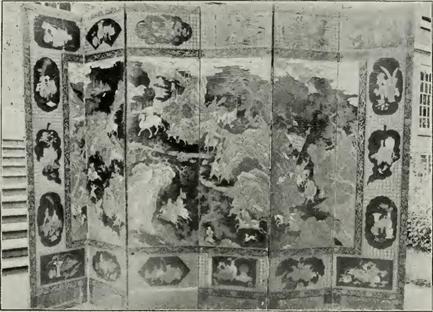

Gov. Elihu Yale's Japanese Screen ------------------------------------------- 128

Plas Grono

------------------------------------------------------------------------- 132

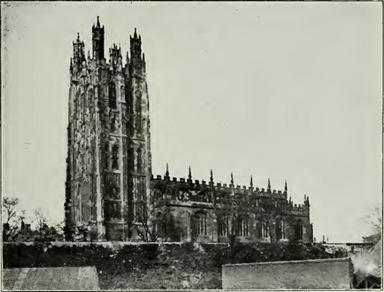

Parish Church at Wrexham------------------------------------------------------ 140

Views at Parish Church of Wrexham ---------------------------------------- 144

Gov Elihu Yale's Tomb (Two Views) --------------------------------------- 152

Photo of Thomas Yale's 'Letter ----------------------------------------------- 160

Views at Yale University (Three Pages)

_ --------------------------------- 168

Linus Yale Sr. --------------------------------------------------------------------- 296

Old Yale Lock Factory ---------------------------------------------------------- 296

Linus Yale Jr ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 436

The Yale Locks and Keys ------------------------------------------------------- 438

The Yale Locks and Keys-------------------------------------------------------- 440

The Yale Lock Factory, 1866 ------------------------------------------------- 440

Factory of Yale and Towne Mfg. Co. --------------------------------------- 442

![]() Residence of J. Hobart Yale _ _ _ ------------------------------------------ 444

Residence of J. Hobart Yale _ _ _ ------------------------------------------ 444

![]() PRINTED AND BOUND BY

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

MILBURN az SCOTT COMPANY

BEATRICE, NEBRASKA

U. S. A.

YALE GENEALOGY

AND

HISTORY OF WALES

![]() The British Kings

and Princes.

The British Kings

and Princes.

![]() LIFE OF OWEN

GLYNDWR.

LIFE OF OWEN

GLYNDWR.

![]() BIOGRAPHIES OF

BIOGRAPHIES OF

GOVERNOR ELIHU YALE

For Whom Yale

University was Named.

LINUS YALE, Sr., and LINUS YALE, Jr.

The Inventors of Yale

Locks.

MAURICE FITZ GERALD;

The Great Leader in the

Conquest of Ireland.

ROGER de MONTGOMERY

The Greatest of the

Norman Lords.

and OTHER NOTED

PERSONS.

![]() BY

BY

RODNEY HORACE YALE.

![]() BEATRICE, NEBRASKA,

U. S. A.

BEATRICE, NEBRASKA,

U. S. A.

1908.

PREFACE.

0

In compiling this work I

have endeavored to present only definite and positive facts, based upon

competent and proven authorities. I was intended that mere fiction and

tradition should have no part in the events recorded herein, and the reader may

be assured that the matter presented is authentic and founded entirely upon

reliable historical, biographical, genealogical and private records.

I have kept well in mind

the fact that the mere assumption, based upon tradition or like unreliable

authority, of descent from or connection with noted historical characters,

should have no place in a work of this class, and the ancient genealogy of the

Yales as presented herein is bereft of all suppositional matter and is a bare

record of facts as established by anciently recorded pedigrees and reliable

historical matter,

The principal

authorities consulted are: "The Welsh People" (1906). by John Rhys,

M. A., Professor of Celtic in the University of Oxford, and David

Brynmor-Jones, member of Parliament, "Burke's Peerage," "Burke's

Landed Gentry," "The Life of Owen Glyndwr," by Bradley,

"Abbeys and Castles of England and Wales," "The Dictionary of

National Biographies," "Country Townships of the Old Parish of Wrexham,"

by Alfred Neobard Palmer, and various Encyclopedias and Histories.

Substantial and valuable

special information was also supplied direct, by Mr. Alfred Neobard Palmer, of

Wrexham, Wales, a recognized authority on Welsh pedigrees and family history,

and by Mr. George F. C. Yale of Pwllheli, Wales, son of Wm. Corbet

Yale-Jones-Parry of Plas yn Yale and Madryn Castle.

The principal original

sources of information pertaining to early Britain, of the authorities named,

are the 'Brut," a history of the British Princes, and "Annales

Cambriae," both being of ancient Cymric origin.

2013190

4 PREFACE

The sources of

information for the genealogy of the Yales after their settlement in America

were, "The Yale Family," by Judge Elihu Yale, "The New Haven

Historical Society Papers," the living Yales themselves, and their

descendants.

I am however especially

indebted to several ladies and gentlemen, who have unselfishly and loyally,

rendered much valuable assistance, in supplying records, information, etc.,

pertaining not only to their own branches, but to other branches as well; among

whom are Miss Amelia Yale, Houseville N. Y., Miss Charlotte Lilla Yale, Meriden

Conn., Miss Fanny I. Yale, Hartford, Mrs. Madeline Yale-Wynne, Chicago, Mrs. C.

C. Xing, Chicago, Mr. J. Hobart Yale, Meriden Conn., Mr. George H. Yale,

Wallingford, Conn., Mr. William T. Yale, New York N. Y., Mr. Fred'k C. Yale,

New York, N. Y., Mr. William Henry Yale, New York, N.Y.,Mr. Washington Yale,

Minneapolis, Minn., Mr. F. B. Yale, Waco, Neb., Mr. D. E. Williams, Reno, Nev.,

Mr. Arthur Yale, Montreal, Canada, and Mr. M. B. Waterman, Buckley, Ills., and

others I also wish to extend thanks to the large number of other members of the

Yale family and descendants, who have unstintingly and carefully supplied the

records pertaining to their own branches; and in connection with these

acknowlegments, I regret that it is necessary to state, that I have found it

impossible to procure from some of the Yale families, whose addresses I have,

the required information regarding their ancestry, to enable me to enter their

family records in this work; although I have made repeated and urgent requests.

I also deeply regret that there are some few whose ancestry I have been unable

to trace, even with their own aid, willingly extended. I mention these facts at

this time, so that it may be understood that the author is not wholly

responsible for the absence of such desirable and essential family records as

may be lacking.

As

many of the early ancestors of the Yales were kings and princes of ancient

Britain and Wales, and others prominent leaders of the Normans in their

conquest of the Principality, I concluded that the most practical way to record

the events in the lives of these important personages and present same in a

connected manner and the order in which they appeared in the national life, was

to write a brief history of ancient Britain and Wales.

In

fact the lives of these ancestors were so intertwined with the na‑

PREFACE 5

tional

life and constituted such an important part of it, that it would be impossible

to write their biographies without also writing a history of Wales; and it

would likewise be impossible to write a history of Wales without writing their

biographies.

Individual biographies are presented of those

ancient ancestors of prominence whose careers were not sufficiently connected

with Welsh affairs so that the principal events of their lives could be told in

connection therewith.

The "Yale Pedigree" presented herein

will make clear the various connections and the several lines of descent. The

names are numbered and these numbers are also inserted in the history of Wales,

in connection with the names of the same persons, where they first appear, and

in some instances the number is inserted successively with the name. Usually,

however, the number is only inserted once, it being expected that the name will

be recognized, as it successively appears in the narrative. The names of the

ancestors in the History are all printed in capitals, to distinguish them from

other names.

The Pedigree numbers are

also used in connection with the "Genealogy of the Ancient Yales"

and the biographies in connection with same_

In reference to the family

records, will state that sometimes dates given me by different members of a

family for the same event would differ. In such cases I have used the date

which seemed most likely correct.

Where no names of children are given it does

not always follow that there were no children, but it means, at least, that no

record of children was sent to me.

Addresses

and dates of death, etc., are usually not given in the records of children,

where the persons have individual family records in the book.

Addresses

given are the last known to the author.

RODNEY HORACE YALE.

![]() INTRODUCTION.

INTRODUCTION.

0

The family name

"Yale" originated in Wales and was formerly spelled "Ial"

and "Yal" and comes from the commote, hundred, or district of Yale,

in Powys Fadog, Wales. The district of Yale, together with the adjoining

district of Bromfield on the west, have formed since the end of the thirteenth

century, a lordship, known as the lordship of Bromfield and Yale. Both

Bromfield and Yale are in the county of Denbigh.

The district of Yale is

an upland plain bounded on all sides by hills and contains the old parishes of

Llandysiles yn Yale, Bryn Eglwys, Llanarmon yn Yale, Llandeg-la yn Yale and

Llanrones. Each parish, except the last named, being divided into townships.

The

ancient Yales were descended from Osborn Fitz Gerald (0 sbwrn Wyddel), of the

country of Merioneth, Wales; and one of his descendents, Ellis ap Griffith,

married Margaret, the heiress of Plas yn Yale, in the lordship of Bromfield and

Yale; and in this way the estate of Plas yn Yale came into the family, and the

descendants of Ellis and Margaret later on definitely adopted the name Yale as

a family surname; and with the exception of the Lloyds of Bodidris, with whom

they were connected, were the most important family in Yale. Thus it will be

seen that the name of Yale, as well as the estate of Plas yn Yale, were derived

from the maternal side of the house. Dr. Thomas Yale, who died in 1577 and who

was Chancellor of Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury and grandson of

Ellis ap. Griffith and his wife Margaret, was the first to definitely assume

the surname of Yale; and his nephews, Thomas Yale and Dr. David Yale (Dr. David

Lloyd), who were respectively the ancestors of the Yales of Plas yn Yale and of

Plas Grono, continued the name.

Surnames

in Wales did not pass from father to son, in the way

8 INTRODUCTION

to which we are now accustomed, until the latter part of

the sixteenth century, and the practice was not definitely settled for a long

time after‑

wards.

Sons usually had for a surname, the given name of the father; however they

often assumed names derived from estates, castles, towns or districts; and as

we have previously noted, the family name "Yale" was derived from the

name of the district of Yale, in the lordship of Bromfield and Yale.

The Yales, although

natives of Wales, were of Italian and Norman, as well as British blood. There

seems however to be no evidence of Saxon stock in the ancestry.

The first ancestor

recorded in the pedigree, in the direct male line, is Dominus Otho, a nobleman

from Florence Italy (a Florentine); but he

was

not the only ancestor of Italian blood, as Cuneda, the head of the long line of

British kings and princes, from whom the Yales are descended on the maternal

side of the house, was no doubt partly of Roman parentage.

The

predominant strain in this ancient ancestry was however undoubtedly British

(Brythonic), as the maternal ancestors were nearly all , if not all, Welsh

(British), except Alice de Montgomery, through whom came the connection with

the Normans.

As regards the personality and rank of these

early ancestors, it can be properly stated that their political and social

standing was on an

equality with the great

nobles and the rulers, of the times. There

are but few, if any,

families among the nobility of any land, that can point to a more honorable and

noble lineage, than that of the Yales; de‑

scended

as they are from the ancient kings and princes of Britain and from the greatest

of all the Norman lords, Roger de Montgomery, (who was of the same family as

William the Conqueror), as well as from Maurice Fitz Gerald, the commander of

the first expediton in the Norman conquest of Ireland.

The

antiquity of the Yale pedigree is equally eminent, dating back as it does, in

the direct male line, to Dominus Otho, the Florentine noble, who came to

England in 1057, nine years before the Norman conquest; and on the maternal

side to Cuneda, the first ruler of the Cymric nation, about the year 415 A. D.

But few noble, or in fact Royal families, can claim greater antiquity.

The

pedigree presented herein will make clear, the connections re‑

INTRODUCTION 9

ferred to, and it will be noted that the Yales are connected

with the House of Cuneda and the succeeding Kings and Princes, through three

distinct maternal lines. One of these maternal ancestors being, Lowrie,

daughter of Tudor Glyndwr (Tudor ap Griffith Vychan), and niece of the

memorable Owen Glyndwr. Her great grandfather, Thomas ap Llewelyn, as will be

noted, was also the ancestor of the five Tudor Kings and Queens of England, and

the present King Edward VII, as well.

Her grandfather GriffithVychan, was

descended also from the Kings and Princes of Wales and the Princes of Powys

Fadog, who lived at Castle Dinas Bran.

Another one of the three Welsh princesses

referred to in the preceding paragraph was Nesta, the "Helen of

Wales," who was not only great in herself and in her ancestry, but great

in her posterity as well.

![]() The third maternal ancestor referred to was,

Gladys, daughter of the Prince of North Wales.

The third maternal ancestor referred to was,

Gladys, daughter of the Prince of North Wales.

In referring to the pedigree and history of

Wales, it will be seen that the ancestors of the Yales, among the Kings and

Princes of Britain and Wales, were mainly the sovereign rulers. Attention is

called to this fact, as there were many under kings and princes of minor

importance, who ruled over smaller territories, which were parts of the whole

and subject to the sovereign king or prince.

![]() In writing the foregoing particulars relative to the

ancient ancestry of the Yales, I am sensibly aware of the prevalent practice

among writers of works of this class, to endeavor to connect the family lineage

with some noted historical character, whether justified in so doing by

authentic records or not, and I realize that many are disposed to scoff at such

claims; however I can do no less than follow the indisputable authorities

bearing on the origin of the Yales and their ancestry and feel a sufficient

justification in presenting the matter set forth, in the absolute knowledge

that it is amply substantiated by competent and reliable records.

In writing the foregoing particulars relative to the

ancient ancestry of the Yales, I am sensibly aware of the prevalent practice

among writers of works of this class, to endeavor to connect the family lineage

with some noted historical character, whether justified in so doing by

authentic records or not, and I realize that many are disposed to scoff at such

claims; however I can do no less than follow the indisputable authorities

bearing on the origin of the Yales and their ancestry and feel a sufficient

justification in presenting the matter set forth, in the absolute knowledge

that it is amply substantiated by competent and reliable records.

![]()

![]() Ancient Pedigrees of

early British Kings and Princes.

Ancient Pedigrees of

early British Kings and Princes.

THE HOUSE OF CtiNEDA.

Brythonic and Goidelic.

From

ANNALES CAMBRIAE.

![]() [O]wen map. iguel. map.

Cein.

[O]wen map. iguel. map.

Cein.

map.

catell. map. Guorcein

map. Rotri. map. doli.

map. mermin. map. Guordoli.

map. etthil map. Duran.

merch. cinnan. map.

Gurdumn

map.

rotri. map. Amguoloyt

map.

Iutgual. map. Aeguerit.

map. Catgualart. map.

Oumun map. Catgollaun. map. Dubun.

map.

Cat man. map. Brithguein.

map.

Jacob. map. Eugein.

map. Bell. map. Aballac.

map. Run. map. Amalech qui

map.

Mailcun. fuit, beli magni

map.

Catgolaun. flies et anna

Iauhir. mater ejus.

map.

Eniaun girt. quanz dicunt

esse

map. Cuneda. [cons°.

map. ,Etern. brina MARLE

map. Patern pefrut uirginis matris

map.

Tacit. d'ni n'ri ih'u

xp'i.

The foregoing is the pedigree of A 20 Owain ab Howel, son of

Howel Da, and as will be noted, carries his genealogy back a very long time: in

fact to Beli et Anna, and the same persons who are the first in pedigree.(X)

OTHER KINGS AND

PRINCES.

Probably Goidelic.

(X) From "ANXALES

CAMBRIAE"

![]() [M]orcant. map. Vrb.

[M]orcant. map. Vrb.

map. Coledauc. an.

map.

Morcant. map. Grat.

bulc. map. lume‑

map.

Cincar. tel.

braut. map. Riti‑

map.

Branhen. girn.

map.

Dumngual. map. Gude‑

moilmut. cant.

map.

Garhani map Ou‑

aun. tigir.

map.

Coyl hen. map. Ebiud.

Guotepauc. map. Eudof.

(Godebog) map. Eudelen.

map.

Tec ma- map. Aballac.

. nt. map. Beli of anna.

map. Teu‑

hant.

map. Telpu‑

.

The above is a very ancient compilation and probably is

a list of Goidelic Kings and Princes from Beli et Anna, to times contemporary

with Cuneda and his more immediate descendants. It will be noted that Coyl hen

,(Coel Hen) (or Coel Godebog), the father of Cuneda's wife, has a place here.

Dyfnwal Moelmud (Dumngual Moilmut) the Cymric law maker, before the time of

Howel Da, is also named in the pedigree.

Other

authorities state that Coel Hen (Coel Godebog) was a King of Britain.

These pedigrees are of

genuinely very ancient origin and in the opinion of eminent authorities, there

is no reason at all to doubt their authenticity. Anna, the earliest of the

line, is said to have been daughter of the Emperor of Rome. It is quite likely

that the earlier portions of these pedigrees, however, are founded, at least

partly, on tradition. "Map" means "son of."

These pedigrees are presented verbatim, as

examples of the character of such documents, from Cymric sources.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() THE YALE PEDIGREE.__

THE YALE PEDIGREE.__

"fg`itaMig.

A 2.

Ifilirmn G..

A 3.

A 4.

A 7. A 0.

CV2ialVatal''

A". TrG.Vorderrnig ?at 2r1Vir.n.=LUV.7.n "e.V.V.2.1".Va.t!, RnInre'deM.X. .S" RI"mxr;,„sluvz,=87,!

"1,5r.i.v"aviLvg "criFgawcvt".!

A'atrf

INE. s.

2nT'rtge:O.7i Cr.

'EV."

DIRECT NIALE L Powy

""trn=4;..- "' C"' 2'. — "n• 2n,,IT..717"7.,!""e

"r

_____________________ I2'

27,211.rd!irit71.7.— D..

.-zgninv.--,,,,re,nsr..

". 11.".3.11="11..41

`"'

'15ZratiVI.4iFr

T..m. P. I.... LI.. —

'1171211415a1771V 'Yglikir;;Yit7rGinEl

— —

· '1./rInFurraTa..- —

— Gn.

—

'1121E:Z7157: " AG.

7...Gr.,

"- — _ -

C (Arm

75/54:tie.

DaGd.

flr.,,,fti.itztzsz,ggn,gfo.,,ttg:mzvwmzgggtmtgztqfiabozmglz.tgaa •

WALES.

0

The Dominion or

Principality of Wales may be described as a broad indented peninsula, situated

in the South Western part of Great Britain. Its greatest length from North to

South is about 135 miles, and its breadth from East to West ranges from 35 to

95 miles. It is bounded on the North by the Irish sea and the estuary of the

Dee, on the West by St. George's

Channel,

on the South by the Bristol Channel and on the East by the English counties:

Cheshire, Shropshire, Herfordshire, and Monmouth‑

shire. The present

Eastern boundary was settled by Henry VIII.

The counties of Wales

are named as follows, with their Welsh equivalents.

Anglesey. Ynys Mon.

Ca

rnar vonshi re. Sir

Gaernarfon.

Denbigshire. Sir Dinbych.

Flintshire. Sir Fflint.

Merionethshire. Sir Feirionyd.

Montgomeryshire. Sir Drefaldwyn.

Becknockshi

re. Sir Frycheiniog.

Cardiganshire. Sir Aberteifi.

Carmarthenshire. Sir Gaerfyrdin.

G

tamorg anshi re . Sir

Forgannwg.

Pembrokeshire. Sir Benfro.

Radnorshire.

Sir Faesyfed.

Monmouthshire. Sir Fynwy.

The first six comprise what is generally

termed North \Vales, and the remainder South Wales. Their boundaries preserve

to some extent

the ancient divisions

of the Principality. There are also two large country boroughs, Cardiff and

Swansea.

Monmouthshire is

technically an English county, but is essentially Welsh in origin, language and

customs. The thirteen counties are divided into "hundreds," poor-law

unions, highway districts, etc. The

![]() most ancient political

divisions were Cantrefs and Cymwds. These land divisions, however, should not

be confounded with the division of the "Cymric," land into small

kingdoms or principalities, among the regal or princely families.

most ancient political

divisions were Cantrefs and Cymwds. These land divisions, however, should not

be confounded with the division of the "Cymric," land into small

kingdoms or principalities, among the regal or princely families.

The geographical boundaries and divisions given by

countries are, as indicated, those of the present day and of later times. The

Wales, or Britain, of more ancient times, in the days of the Romans and for

several centuries thereafter, comprised a large part of what is now Great

Britain. Extending from the Bristol Channel on the South, to the Clyde and the

Forth on the North, including as well the South Western peninsula.

Wales is quite

mountainous, particularily in the North, where Snowdon, the culminating point

of South Britain, rises to a height of 3571 feet. It is rich in minerals,

particularily copper, coal and iron. Has many beautiful lakes and numerous

rivers, also many fertile valleys.

The Welsh cherish their

ancient Brythonic, or Cymric (Celtic) language, with great affection and it is

quite generaly in use among the people at the present time. In 1891 there were

508,000 persons in Wales who habitually spoke only Welsh; 402,000 who spoke

both Welsh and English, and 759,000 who spoke only English.

In

Welsh "C" has always the sound of "K," however the present

Welsh alphabet does not recognize "K".

"G" never has

the English sound of "J" or "dzh," as in John or James.

"F" is sounded "V", but "V" is not included in

the modern Welsh alphabet.

"D" has the

sound of "th" in the English words "this"

and"that". "Ll" is a simple and single consonant.

"R"

is trilled as in Italian, and in "rh", it is a surd strengthened by

the aspirate.

"5"

is never sounded "Z."

"W"

and "I" may be either vowels or consonants.

"U" is sounded like "i" in the word

"bit", and so sometimes is "Y." Thus "Gruffyd" or

"Gruffud" is sounded and spelled in English "Griffith."

The literature of the Welsh is of considerable consequence

and note, but the compositions of their Bards are the most celebrated and best

known. These poetry making singers had an important part in the national life

of ancient Wales.

WALES 13

The earliest laws of

Wales, of which we have the most definite knowledge, were established and

promulgated by Howel Da (Howel the Good), one of the ancient Kings of all

Wales, about 942; and that they were good laws and loved by the people, is well

evidenced by the fact that they remained in force throughout Wales, practically

uninterruptedly, until the conquest of Edward I. in 1282, a period of 340

years, and in some sections for a much longer time. It is stated that Howel

summoned four "laics" and two "clerics" from each commote

in his dominions, to meet at Ty Gwyn and that this assembly, under his

direction and guid‑

ance, formed these laws.

These codes deal first

with the organization of the household of the King. Howel appointed the

following servants of the court:

Chief of the Household.

Priest of the

Household.

Steward.

Chief Falconer.

Judge of the Court.

Chief Groom.

Page of the Chamber.

Bard of the Household.

Silentary.

Chief Huntsman.

Mead Brewer.

Mediciner.

Butler.

Door Ward.

Cook.

Candle-bearer.

Including eight

officers of the queen:

Steward.

Priest.

Chief Groom.

Page of the Chamber.

Handmaid.

Doorward.

Cook.

Candle-bearer.

The rights, privileges

and duties of these officers were set out in great detail. The Chief of the

Household was required to be of the royal blood.

![]() Besides these twenty-four officers, there

were eleven servants of the household, i. e.:

Besides these twenty-four officers, there

were eleven servants of the household, i. e.:

Groom of the rein.

Foot holder. Land Maer. Apparitor. Porter.

Watchman. Woodman. Baking woman.

Smith of the Court.

Chief of song. Laundress.

There was also a

"table of precedence," which went into much detail.

The near relations of

the king formed an exclusive, royal class. Next in rank werethe nobles or

"highmen"; then the bonedigion, (gentlemen); and then the unfree

persons; and finally a class of menial or domestic slaves, which of course was

the lowest class of all.

Courts were established

by these laws, judges appointed and minute and detailed regulations were made,

for the duties, rights and privileges of the people and for the enactment of

justice in all things and in all matters, according to the views and ideas of

these ancient lawmakers, which were evidently wise and just in the eyes of the

people, who fondly cherished the laws which they promulgated, for many

centuries and fought numerous, desperate and bloody battles for their

retention, as

against

the English laws, which their enemies sought to enforce upon them.

HISTORY

OF WALES

AND

The Kings and Princes.

![]() (Names of Ancestors of

the Vales are in Capitals. Note the pedigree numbers.)

(Names of Ancestors of

the Vales are in Capitals. Note the pedigree numbers.)

Wales of to-day

represents and for many centuries past has represented, in its people,

language and customs, what remains of ancient Britain and the Brittones or

Britons (British). The British Isles (Great Britain and Ireland) were first

peopled by an Aboriginal race, perhaps the Picts, then came the Goidels in the

sixth century before the Christian era, or before; a branch of the Celts of the

Aryan race, who spread over perhaps most of what is now England, and Scotland,

before they were pressed and attacked by the Brythons or Britons, who came in

about the a second century before Christ. The Brythons wereanother branch of

the Celts, speaking a different yet related language and having customs and

usages not known to the Goidels. The language of the Goidelic, is represented

at this time by the Gaelic of Ireland, of the Isle of Man and of Scotland,

while the Brythonic is now represented by the Welsh. The British tribes called

Silures, Dimette and Ordovices were of Goidelic or Brythonic Stock.

These early Celtic

tribes had a long line of British Kings who were very important in their day,

both before and after the coming of the Romans to Britain. Julius Cwsar led the

Romans in their first invasions in the years 55 and 54 B. C. and in the year

43 A. D.,

they began an

aggressive campaign which resulted finally about the year 78 A. D. in Roman

supremacy throughout the greater part of Britain. The Romans governed the

country and protected the inhabitants from other invaders in their accustomed

aggressive way. They built, about the

![]() year 120 A. D., a wall

from the Solway to the Tyne, called "Hadrian's Wall," after Emperor

Hadrian; and about the year 143 his successor built a turf wall from the Clyde

to the Forth, which was rebuilt in masonary in 208 by the Emperor Severus.

These walls were constructed for protection against the warlike tribes in the

North. The civil administration of Roman Britain was practically subordinate

to the military system. The head of the civil organization was called, Vicar

of the Britannias (Vicarius Britanniarum). The military command was distributed

as follows: the Count of Britain, who had command of a body of troops not fixed

to any particular locality; The General or Duke of Britain (Dux Britanniarum)

or (Dux Britannia) who had command of the

troops on the Wall and in the country south of it to the Humber; and the Count

of the Saxon Shore, who had charge of the south east part of the island.

Britain was treated as a single Roman province until the year 210. when Severus

divided it into two, called Lower and Upper Britain. In 297,Diocletian divided

it into four provinces and in 369 a fifth was made, called Valentia.

year 120 A. D., a wall

from the Solway to the Tyne, called "Hadrian's Wall," after Emperor

Hadrian; and about the year 143 his successor built a turf wall from the Clyde

to the Forth, which was rebuilt in masonary in 208 by the Emperor Severus.

These walls were constructed for protection against the warlike tribes in the

North. The civil administration of Roman Britain was practically subordinate

to the military system. The head of the civil organization was called, Vicar

of the Britannias (Vicarius Britanniarum). The military command was distributed

as follows: the Count of Britain, who had command of a body of troops not fixed

to any particular locality; The General or Duke of Britain (Dux Britanniarum)

or (Dux Britannia) who had command of the

troops on the Wall and in the country south of it to the Humber; and the Count

of the Saxon Shore, who had charge of the south east part of the island.

Britain was treated as a single Roman province until the year 210. when Severus

divided it into two, called Lower and Upper Britain. In 297,Diocletian divided

it into four provinces and in 369 a fifth was made, called Valentia.

The affairs of the Roman

Empire required, finally, early in the fifth century, the support of all her

legions at home, and in the year 410, the Roman troops and Roman authority were

withdrawn from Britain and the Emperor of Rome concerned himself no more with

the affairs of the island.

After

the departure of the Romans the inhabitants seem to have maintained a more or

less successful resistance against the ravages of the Picts and Scots of the

North, but according to the Saxon narrative, they were finally induced to seek

the aid of the Saxons, to repel these ferocious Northern neighbors, and three

ships with 1600 men were sent to them under the command of the Saxon brothers

Hengest and Horsa, about the year 449. A complete victory was soon

obtained against the foe and then the Saxons turned their arms against the

Britons; thus commencing the Saxon conquest of Britain, which was bitterly

contested for more than 150 years. The Saxons were aided by other Teutonic

(German) tribes, the Angles (English) and lutes, and finally in this period

named, gained supremacy over all of Britain except Strathclyde, (a medieval

British Kingdom comprising parts of Southwestern Scotland and Northwestern

England), Wales and West Wales, (Cornwall). The resistance of the Britons was

determined, tenacious and heroic, bit‑

![]()

![]()

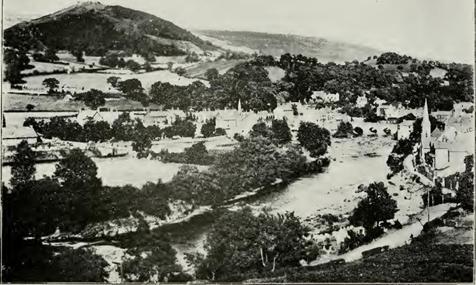

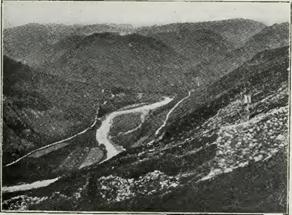

![]() LLANGOLLEN, NORTH WALES,

AND CASTLE DINAS BRAN.

LLANGOLLEN, NORTH WALES,

AND CASTLE DINAS BRAN.

The ruins of the castle

may be noted on top of the hill in the distance, at the left.

![]() terly contesting every

foot and every inch to the last extremity, with a ferocious and aggressive foe,

undoubtedly greatly superior in numbers as well as in equipment. The Saxon

conquest of Britain was different, or had different results, than that of any

other conquest known to history. In other conquests a considerable portion of the

conquered people have remained with the land and become assimilated by the

conquerors, but with these Britons it was not so; when finally compelled to

yield to the force of arms, practically the entire population left their homes

and the land and retreated with their fighting men, leaving to the conquerors

uninhabited and also, no doubt, devastated territory. These results of the

struggle account for the fact that the population of England offers no

evidence, generally speaking, of the assimilation of Celtic blood, while the

population of Wales, to which the Britons were mainly finally driven, is

predominately British (Celtic). The term "Brittones" yields in Welsh

the name "Brython," a "Briton or Welshman."

terly contesting every

foot and every inch to the last extremity, with a ferocious and aggressive foe,

undoubtedly greatly superior in numbers as well as in equipment. The Saxon

conquest of Britain was different, or had different results, than that of any

other conquest known to history. In other conquests a considerable portion of the

conquered people have remained with the land and become assimilated by the

conquerors, but with these Britons it was not so; when finally compelled to

yield to the force of arms, practically the entire population left their homes

and the land and retreated with their fighting men, leaving to the conquerors

uninhabited and also, no doubt, devastated territory. These results of the

struggle account for the fact that the population of England offers no

evidence, generally speaking, of the assimilation of Celtic blood, while the

population of Wales, to which the Britons were mainly finally driven, is

predominately British (Celtic). The term "Brittones" yields in Welsh

the name "Brython," a "Briton or Welshman."

As before indicated, the

portions of Britain as yet unconquered by the end of the sixth century, or

about the year 600, comprised the entire western part of the island, from the

river Clyde in Scotland, to the English Channel; this territory being

represented by Strathclyde, afterwards called Cumbria, a Cymric (British)

Kingdom, the Kingdom or Principality of Wales and West Wales (now Cornwall);

and as will be seen by reference to current maps, it comprised, in addition to

all of Wales of the present day, and all of England on the Western and

Southwestern coasts, a large part of Southwestern Scotland as well.

This

large remaining British territory was not however intact as late as the year

600, as the Britons of Cornwall, Devon, Somerset and Gloucester, had been

permanently severed from the Britons of what is now Wales, by the Saxon victory

at the battle of Deorham in the year 577.

The desperate struggle

continued, the Saxons, Engles (Angles, or Englishmen) and Jutes were met by

courage and valor equal to their own, no territory was given up by the Briton

or gained by the conqueror, until the price had been paid in the blood of the

contestants. As each bit of ground was torn away by the stranger, the Briton

sullenly withdrew from it, only to turn and fight doggedly for another.

The

next event of great historical importance was the battle of Chester in 616,

(the date given by Saxon writers is 607, but 616 seems more likely correct,

according to Celtic authority.) At this battle 2000 British monks,

![]() from Bangor Icoed

Monastry, who stood apart from their army, with arms outstretched in prayer,

were ruthlessly slaughtered by the English or Saxons, under .thelfrith. This

victory of the English was complete, and by the fall of Chester, which stood at

the juncture of the British Kingdoms of Wales and Cumbria, the Welsh were

permanently cut off from their northern allies, and Britain as a single

political body practically ceased to exist; the British territories of Wales,

Cumbria and Cornwall, having been permanently segregated from each other by

conquest.

from Bangor Icoed

Monastry, who stood apart from their army, with arms outstretched in prayer,

were ruthlessly slaughtered by the English or Saxons, under .thelfrith. This

victory of the English was complete, and by the fall of Chester, which stood at

the juncture of the British Kingdoms of Wales and Cumbria, the Welsh were

permanently cut off from their northern allies, and Britain as a single

political body practically ceased to exist; the British territories of Wales,

Cumbria and Cornwall, having been permanently segregated from each other by

conquest.

Before proceeding

further with the narrative it is best to deal briefly

with the political organization of the Britons after the

departure of the i

Romans. It seems likely

that they must have for a time endeavored to maintain the offices of authority

to which they had been accustomed for several centuries under Roman domination;

however, it is probable that the actual government was administered mainly by a

number of sub-kings or princes, over their respective tribes. It is definitely

known, however, that sometime after the Romans left, the Britons in the western

portions of the island, comprising Cumbria, Wales and perhaps Cornwall and

other sections, from the Clyde in the North to the English Channel on the

South. organized themselves into some sort of a confederation known as the

"Cymry." It is impossible to state when the national life of the Cymry

began, but its inception was no doubt partly due to the assumption of the

authority of the Brythons over the Goidels and partly to the necessity of

organization of these two branches of Celts to withstand the encroachments of

the Saxons, Angles and Jutes. At any rate they considered themselves

collectively as one nation, from the time they recognized the term Cymry and

acknowledged the over-lordship of a king or ruler who was called the

"Gwledig-,

" and whose office, or dignity, was sooner or later known as the

"Crown of Britain." The authority of the gwledig appears to have been

partly based upon his claim to be the successor of the Roman officer called the

Dux Britanniarum, and partly on earlier tribal notions of political and

military organization. In time the territory over which the confederation

spread came to be called "Cymru" and the predominant language,

"Cymraeg." However the national terms were "Britain" and

"Britons," until the territory was finally reduced to the confines of

Wales, and even much later; in fact until about 1135.

The word Cymro means

"compatriot" and also "Welshman;" the plural being

"Cymry."

![]() As regards the rulers

or kings in Britain subsequent to Roman occupation, the names of Vortigern and

King Arthur are prominent in the English histories; the former in connection

with the Hengest and Horsa narrative and the latter in connection with heroic

exploits pertaining to the struggles of his countrymen with the Teutonic

tribes. The Celtic authorities do not seem to disclose anything especially

definite as to the careers of either of these characters, as regards the parts

they took in actual events, or the territory over which they ruled.

As regards the rulers

or kings in Britain subsequent to Roman occupation, the names of Vortigern and

King Arthur are prominent in the English histories; the former in connection

with the Hengest and Horsa narrative and the latter in connection with heroic

exploits pertaining to the struggles of his countrymen with the Teutonic

tribes. The Celtic authorities do not seem to disclose anything especially

definite as to the careers of either of these characters, as regards the parts

they took in actual events, or the territory over which they ruled.

In any event the

earliest ruler of this British organization, or of the Cymry and of

"Cymru" (the land of the Cymry) of which there is distinct evidence

from Cymric sources, was (A 1) CUNEDA, whose name is well known to Welsh

literature. In fact, the beginning of the history of the Cymric nation, as an

independent political body, must be associated with the migration into North

Wales of a Brythonic tribe, whose chief was this CUNEDA WLEDIG, (the ruler) and

who established his rule over Wales, and united the Celtic tribes of the west

of Britain into a kind of confederation under his leadership. This was soon

after the Romans left Britain, perhaps about the year 415 A. D., and before the

beginning of the Saxon or Teutonic conquest of Britain.

CUNEDA was the son of

iEtern (lEternus), who was son of Patern Pesrut (Paternus of the Red Tunic).

"The Red Tunic" probably had reference to the purple of office.

Patern Pesrut was son of Tacit (Tacitus). CUNEDA'S ensign was a "Red

Dragon," which came with the title of Dux Britannia , from the Romans, and

it was the standard of the rulers of Britain and Wales for many centuries after

him. The title Dux Brittonum afterwards became Rex Brittonum, or king. His wife

was daughter of Coel Hen (Coel Godebog), who was of the line of ancient British

Kings who ruled in Britain before the Romans came to the island. It seems

certain that CUNEDA'S family were Christains and perhaps partly of Roman

descent.

CUNEDA and his sons

were no doubt the founders of the British or Cymric fnIation, which arose after the Romans left

Britain, and the inception of this national confederation of the British

tribes under one ruler, was no doubt partly due to the necessity of such an

organization to combat the encroachments of the Teutonic tribes which began, as

before stated, about 449.

CUNEDA had held after the departure of the Romans, the

title and au‑

![]() thority of the Dux

Britanniae, and this office seems to have represented the predominant military

authority in the island. He was in immediate command of the troops on the Roman

wall after the Romans went away, but later, in response to appeals from North

Wales, he marched there with his troops and expelled the Goidels and Scots from

that territory, and organized a government, which sooner or later spread its

authority over all of Wales and other portions of Western Britain, comprising

most if not all, of the western territory, from the English channel on the

South to the River Clyde in the North.

thority of the Dux

Britanniae, and this office seems to have represented the predominant military

authority in the island. He was in immediate command of the troops on the Roman

wall after the Romans went away, but later, in response to appeals from North

Wales, he marched there with his troops and expelled the Goidels and Scots from

that territory, and organized a government, which sooner or later spread its

authority over all of Wales and other portions of Western Britain, comprising

most if not all, of the western territory, from the English channel on the

South to the River Clyde in the North.

The authority of CuNEDA

as ruler (the "Crown of Britain") descended to his sons, and thus was

founded a dynasty, which retained its sovereignity until the death of Llewelyn

in 1282, a period of nearly 900 years; becoming one of the very oldest Royal

families of western Europe. The rule of the family of CUNEDA no doubt continued

over western Britain in the larger sense for a very long time, as his great

great grandson (AS) MAELGWN, exercised sway over the whole of the country from

the Firth of Forth to the Severn Sea, about the years 535 to 570, and the

sovereignity of the family was not likely materially lessened until the battles

of Doerham in 577 and of Chester in 616, and not finally reduced to the

confines of Wales until the defeat and death of (A 10) King CADWALLON in 635

and in the defeat of his son (A 11) King CADWALADR THE BLESSED in the year 664.

Anyway, Maelgwn's son (A6) RHUN, seems to have maintained the family prestige

over the larger territory during his reign. CADWALADR is said to have been the

last Cymric King (King of the Britons) to wear the "Crown of

Britain," and this is no doubt true as regards sovereignity over the Cymry

of Britain outside of Wales, for it is certain that after his defeat the

authority of the descendents of CUNEDA, as rulers, did not extend beyond the

borders of Wales, for any settled period of time. King CADWALLON, the father of

CADWALADR, was great great great grandson of King Maelgwn

cun),

and the latter was, as before stated, great great grandson of CIINEDA.

From the death of

CADWALADR in 664 to the death of Gruffvd ab Llewelyn in 1063, a period of about

400 years, the authentic history of Wales affords but few details pertaining to

national events; the records seem to have preserved the names of a line of

kings or princes, with only brief accounts of their deeds, consisting

principally of battles and skir‑

![]() mishes with their English

and Danish foes, and between their own tribes.

mishes with their English

and Danish foes, and between their own tribes.

The Cymric nation in

passing to the sons of CIINEDA, of which-There were nine, (some authorities say twelve)

was divided into a number of Kingdoms or principalities and the Kingdom of

North Wales (Gwyned), seemed from the earliest organization to have had a sort

of over-lordship over the others. The King of Gwyned was also the King of the

Cymric nation, when the Cymry first emerged into history, and also when Cymru

territory covered practically all of Western Britain, from the Clyde in present

day Scotland in the North, to the English Channel on the South; as well as

afterwards, when the land of Cymru had been reduced to the boundaries of Wales.

Therefore it will doubtless be understood that Wales consisted of a number of

small kingdoms or principalities, each of which had its King or Prince, subject

in a way, to the over-lordship of the King of Gwyned, who was by inheritance,

the King of the Cymry and therefore of Wales. All of these Welsh Kings and

princes, from the greatest to the smallest, owed their authority to their

descent from CIINEDA, or by virtue of marriage to his descendants.

The quarrels of the Welsh

rulers were numerous and frequent, also oftentimes sanguinary and certainly

continued; as there were doubtless but few years free from civil strife, during

the long period from CADWALADR'S death in the year 664, to the final

extinction of Welsh independence in 1282, a stretch of 618 years. Who would say

that there is not a probability that Welsh independence might have continued

to the present day, had it not been for this weakening civil strife.

The ancient principal

divisions of Wales were Gwyned, (North Wales) Powys (Mid-Wales), and South Wales

(sometimes called Deheubarth). These three principal divisions were also

sub-divided into small principalities or kingdoms, such as Mon, Powys Fadog,

Dyfed, Gwent and others, each having its own king or prince. All of the rulers

of these principal divisions and sub-divisions being, as before stated, according

to the ancient theory of the government of the Cymric nation, subject to the

over-lordship of the King of Gwyned. This authority was sometimes almost

absolute, or at least quite definite, and at other times quite nominal, being

in fact known almost only in theory, for sundry periods.

The

Rulers of Gwyned immediately succeeding CADWALADR were,

![]() according to the most

trustworthy evidence, successively, (A 12) IIITGUAL (also called Idwal Ywrch) who

reigned until 720; (A 13) RHODRI MOLWYNOG (called King of the Britons), who

died in 754; (A 14) KYNAN or CYNON (called also Conan Tindaethwy) who died in

817; (A 15) ESYLLHT (or Etthil) a daughter of Cynon, who married Merfyn Frych

and reigned until the year 841; and their son (A 16) MERFYN FRITH (or Mermin), who died in

battle with the English in 844. Then came Rotri, or (A 17) RHODRI MAWR,

(RODERICK the Great). "Mawr" means in Engligh "the Great."

RuopRi was one of the greater rulers of Wales. He was the hereditary Kingof

Gwyned, and in addition to whatever ancient authority this position held, he

also became through his wife, daughter of Meurig ab Dyfnwal, King of

Ceredigion, lord over part of South Wales, and through his grandmother Nest,

ruler over Powys. He fought many battles with the Mercians and Danes, and in

877 he was slain in battle with the Saxons. He is said to have been absolute

ruler over all of Wales and while he was descended from CIINEDA, it is also

stated in Burke's Landed Gentry, page 1328, of 1906, that he was descended

from Coel Godebog, 75th British King, and Beli Bawr, sovereign of Britain, and

this is confirmed by the ancient pedigree herein, as well as by other

authorities. After his death, three of his sons assumed authority over his

possessions. His son (D 18) ANARAWD had North Wales, another son (A 18) CADELL,

had South Wales and the third son Merfyn, had Powys. They were called "the

three diademed princes."

according to the most

trustworthy evidence, successively, (A 12) IIITGUAL (also called Idwal Ywrch) who

reigned until 720; (A 13) RHODRI MOLWYNOG (called King of the Britons), who

died in 754; (A 14) KYNAN or CYNON (called also Conan Tindaethwy) who died in

817; (A 15) ESYLLHT (or Etthil) a daughter of Cynon, who married Merfyn Frych

and reigned until the year 841; and their son (A 16) MERFYN FRITH (or Mermin), who died in

battle with the English in 844. Then came Rotri, or (A 17) RHODRI MAWR,

(RODERICK the Great). "Mawr" means in Engligh "the Great."

RuopRi was one of the greater rulers of Wales. He was the hereditary Kingof

Gwyned, and in addition to whatever ancient authority this position held, he

also became through his wife, daughter of Meurig ab Dyfnwal, King of

Ceredigion, lord over part of South Wales, and through his grandmother Nest,

ruler over Powys. He fought many battles with the Mercians and Danes, and in

877 he was slain in battle with the Saxons. He is said to have been absolute

ruler over all of Wales and while he was descended from CIINEDA, it is also

stated in Burke's Landed Gentry, page 1328, of 1906, that he was descended

from Coel Godebog, 75th British King, and Beli Bawr, sovereign of Britain, and

this is confirmed by the ancient pedigree herein, as well as by other

authorities. After his death, three of his sons assumed authority over his

possessions. His son (D 18) ANARAWD had North Wales, another son (A 18) CADELL,

had South Wales and the third son Merfyn, had Powys. They were called "the

three diademed princes."

Before continuing with

the succession of events, it is best to state that Offa of Mercia, (King of one

of the Saxon or English Kingdoms), in 757 to 776 and later, engaged in fierce

contests with the Welsh, and about 776 built the famous Offa's dyke, a wall of

earth, from about the estuary of the Dee to the mauth of the Wye; which was

recognized for a time as the boundry line of Cymru. Also it is well to state at

this time, that about the years 809-817, Ecgbryht the Saxon King, subdued the

Cymric Kingdom of Cornwall, which had been separated from the Cymry of Wales in

577, by the battle of Doerham.

Returning to RHODRI'S

successors: ANARAWD ruled in Gwyned for 38 years. His palace was at Aberfraw,

Anglesey. He died in 915 and was succeeded by his son (D 19) IDWAL VOEL, whose

wife was his cousin Avandreg, daughter of Merfyn, King of Powys. ANARAWD

defeated the Saxons in a great battle near the Conway in 880.

![]() CADELL, King of South

Wales, or Deheubarth, whose palace was Castle Dinefwr or Dynevor, in

Carmarthenshire, South Wales, died some years before his brother ANARAWD, about

907, and was succeeded by his son (A 19) BOWEL, afterwards called (A 19) BOWEL

DA, (Howel "the Good.") There is no record of Merfyn's descendants

retaining any claim to Powys. During the reigns of IDWAL and HOWEL almost

universal peace prevailed in Wales. IDWAL was however killed in battle with

the English in 943 and his cousin HOWEL DA, became his successor, as King of

Gwyned; thus becoming the ruler over both North and South Wales and the

"King of the Britons"; or putting it in another way, King of Cymru.

CADELL, King of South

Wales, or Deheubarth, whose palace was Castle Dinefwr or Dynevor, in

Carmarthenshire, South Wales, died some years before his brother ANARAWD, about

907, and was succeeded by his son (A 19) BOWEL, afterwards called (A 19) BOWEL

DA, (Howel "the Good.") There is no record of Merfyn's descendants

retaining any claim to Powys. During the reigns of IDWAL and HOWEL almost

universal peace prevailed in Wales. IDWAL was however killed in battle with

the English in 943 and his cousin HOWEL DA, became his successor, as King of

Gwyned; thus becoming the ruler over both North and South Wales and the

"King of the Britons"; or putting it in another way, King of Cymru.

HOWEL DA was the law maker

of Wales. The ancient Welsh laws were compiled by him and under his direction,

about the years 942-950, He died in 950 after a long, peaceful and prosperous

reign. He was a great and good king. His wife was Elen, daughter of Ioumare ab

Hymeid, King of Dyfed.

Peace disappeared from

Wales with the death of HOWEL DA, and for the next 113 years, until the death

of Gruffyd ab Llewelyn in 1063, sanguinary strife with the English and Danes

and between the Welsh princely families, was almost incessant. There was war at

once between (A 20) OWAtN, Dyfnwal, Rhodri and Edwyn, the sons of HOWEL, on

one side, and Ieuaf and lago the sons of Idwal Voel, on the other, for the

possession of North Wales. HOWEL'S sons were defeated at a battle at Carno in

950 and Ieuaf and Iago assumed joint authority over Gwyned, setting aside the

rights of an elder brother, (D 20), MEURIG ab IDWAL VoEL, whom they blinded and

imprisoned. The sons of Howel however again invaded Gwyned in 954, but were a

second time defeated in a battle at Llanrwst by the sons of Idwal, who in

return then invaded South Wales, but were driven back with great slaughter.

BOWEL'S four sons, as will

be understood, succeeded to the Kingdom of Deheubarth (South Wales), but lost

whatever rights they had in North Wales, by defeat in the battles mentioned.

Dyfnwal, Rhodri and Edwyn soon died (about the years 951-953) and (A 20) OWAIN

ab HOWEL reigned alone until his death in 987 or 989. OWAIN'S long reign of

about 37 years was not especially eventful; there were the usual raids of the

Danes to contend against and some conflicts with the English; also some raids

conducted by his sons (A 21) MAREDYD and (C 21) EINEON, for the ex‑

![]() tension of territory. He was succeeded in

Deheubarth by his son (A 21) MAREDYD ab Owain.

tension of territory. He was succeeded in

Deheubarth by his son (A 21) MAREDYD ab Owain.

. In Gwyned the brothers

Ieuaf and Iago had quarrelled and Iago seized Ieuaf and caused him to be

blinded and then hanged; but Ieuaf had a son Howel, who soon avenged his

father's death by expelling Iago and taking possession of Gwyned himself in the

year 972. Iago was captured by the Danes in 978 and nothing more is heard of

him. This Howel ab Ieuaf, also called Howel Drwg, (meaning Howel the Bad) soon

had to contest for his kingdom with Kystenin or Cystenin, a son of Iago, who

was aided by Godfrey, son of Harold of England; but Howel defeated them at

Hirbarth, and Kystenin was slain. In 984 Howel was killed by the "Saxons

through treachery," He left two sons, Maig, who was killed in 985, and

Cadwallon, who took possession of Gwyned, but he also was almost immediately

defeated and killed in battle by MAREDYD ab OwAIN, King of Deheubarth. Thus

again the Kingdoms of Deheubarth (South Wales) and Gwyned (North Wales) were

united under one head; however MAREDYD'S rule over Gwyned seems to have been

only nominal. It is stated that he also ruled in Powys by right of his mother,

and he is placed by Caradog, an eminent Welsh authority, in the line of the

kings or princes who ruled over all Wales. He was chiefly occupied in

engagements with the Danes and in attacks on Gwyned and Morgannwg, and he

fairly maintained in very disturbed times, the prestige of the house of HOWEL

DA. He died a natural death in 998 or 999, leaving only one child, a daughter,

(A 22) ANGHARAD, who married Llewelyn ab Seisyllt, and also later on, Cynfyn.

The former by right of his wife, assumed the government of Deheubarth.

Returning to the affairs

of Gwyned we find that (D 21) IDIVAL a son of Meurig, who was a son of IDWAL

VOEL and brother of Ieuaf and Iago, had returned in 992 and claimed the Kingdom

from MAREDYD ab OWATN, and was successful in a battle with Maredyd's sons in

993, whereby he wrested MAREDYD'S authority in North Wales from him and became

king of that domain. He did not enjoy his success long, however, for he was

killed, supposedly by the Danes, in 995. He left a young son (D 22) IAGO who

was put aside for a time, but many years later finally became ruler over

Gwyned.

Following the death of

(D 21) IDwAL ab MEURXG, Cynan ab Howel and Aedan ab Blegored, also others,

aspired to the rule of Gwyned.

![]() Cynan was killed in

battle in 1003 and Aedan and his four sons were killed in 1016 in a fight with

Llewelyn ab Seisyllt, who as we have seen, was King of Deheubarth; and thus

again these two kingdoms were brought under one ruler. With the reign of

Llewelyn began a fresh growth of Cymric power, which attained its greatest

development in the reign of his son Gruffyd ab Llewelyn. The English and Danes,

who had harrassed the Welsh for so many of the preceding years, were very busy

with their own affairs in England at this time and the Cymry were therefore

afforded some relief from their attacks, for a considerable period.

Cynan was killed in

battle in 1003 and Aedan and his four sons were killed in 1016 in a fight with

Llewelyn ab Seisyllt, who as we have seen, was King of Deheubarth; and thus

again these two kingdoms were brought under one ruler. With the reign of

Llewelyn began a fresh growth of Cymric power, which attained its greatest

development in the reign of his son Gruffyd ab Llewelyn. The English and Danes,

who had harrassed the Welsh for so many of the preceding years, were very busy

with their own affairs in England at this time and the Cymry were therefore

afforded some relief from their attacks, for a considerable period.

Furthermore, during this

period, in 1016, Cnut the Dane, became King of England and he wisely exerted

himself to promote trade and manufacturing, rather than war, and the incursions

of the Danish marauders from the sea ceased entirely.

It is stated that

Llewelyn also ruled over Powys, but it is not positively certain that he did,

at any rate he was the ruler of both Gwyned and Deheubarth for a number of

years, with great credit to himself, and during a period of prosperity among

his people. There were two rebellions in South Wales during his reign, in 1019

and 1020, both of which were promptly subdued. Llewelyn died in 1023 at the

height of his power. He left a son, Gruffyd, who took an important part in

affairs later, but during the earlier years after Llewelyn's death, IAGO the

son of IDWAL AB MEURIG, mentioned in a preceding paragraph, became ruler over

Gwyned, and Deheubarth was siezed by Rhyderch ab Iestyn. The latter was slain

by Irish-Scots in 1031 or 1033 and Howel and Maredyd, sons of Edwin, who was

son of Eineon, a grandson of HOWEL DA, took his place, and although the sons of

Rhyderch revolted and a battle was fought a year later at Hiraethwy, they

retained the kingdom. Meredyd however was soon afterwards killed in an obscure

conflict, and Howel was left in sole possession of Deheubarth.

Some six years after

these events, in the year 1037, Gruffyd ab Llewelyn, the young son of Llewelyn

ab Seisyllt, who had however reached manhood, asserted his rights and attacked

IAGO, King of Gwyned, and slew him and seized his kingdom; this attack,

however, seems to have been incited by Iago having given protection to one

Iestyn ab Gwrgant, who had ravished Arden, Gruffyd's cousin, a daughter of

Robert ab Seisyllt, and then fled to him. Gruffyd immediately supplemented his

assumption of rule over Gwyned with other aggressive campaigns and the

![]() Cymry suddenly

developed, under his leadership, a military capacity and power which had not

been displayed for centuries; and during his reign reached greater strength

than had before been attained since Cad waladr. He united the forces of Wales

under his leadership, after having brought the other Welsh Kingdoms under his

rule, and became a factor of considerable importance in the affairs of the

whole island, and a dangerous and powerful foe to the King of England. He led

several campaigns into England; the first was into Mercia in 1039, where he

defeated the English in a battle at Rhyd-y-Groes on the Severn, in which

Edwine, brother of Earl Leofric of Mercia, was slain. Afterwards he formed an

alliance with Earl Leofric and married his granddaughter, Ealdgyth, daughter of

his son YElfgar, who in later years became the wife of Harold II. of England.

Cymry suddenly

developed, under his leadership, a military capacity and power which had not

been displayed for centuries; and during his reign reached greater strength

than had before been attained since Cad waladr. He united the forces of Wales

under his leadership, after having brought the other Welsh Kingdoms under his

rule, and became a factor of considerable importance in the affairs of the

whole island, and a dangerous and powerful foe to the King of England. He led

several campaigns into England; the first was into Mercia in 1039, where he

defeated the English in a battle at Rhyd-y-Groes on the Severn, in which

Edwine, brother of Earl Leofric of Mercia, was slain. Afterwards he formed an

alliance with Earl Leofric and married his granddaughter, Ealdgyth, daughter of

his son YElfgar, who in later years became the wife of Harold II. of England.

Gruffyd was on friendly terms with Edward

the Confessor, King of England, and secured from him a grant of all the lands

west of the Dee, that had formerly been possessed by the English.

In 1052 he again

invaded England and fought a battle with "the landsmen as well as the

Frenchmen of the Castle" in Hereford near Leominster, inflicting

considerable loss on his enemies.

In 1055 his

father-in-law, YElfg-ar, Earl of Mercia, was outlawed and fled to Ireland,

returning to Gruffyd in Wales with a fleet of eighteen ships, they invaded

England at the head of a great force, defeated the English under Ralph the

Earl, near Hereford, with great slaughter. Then took and burned Hereford and

slew the priests who were in the church, retiring with much booty. Harold's son

Godwine, was then made Earl in Ralph's place and a great English army was

gathered; but Gruffyd evaded a conflict. Negotiations were then taken up

between Harold and 2Elfgar and Gruffyd. 2Elfg-ar was in-lawed as Earl

and Gruffyd gave up the lands West of the Dee, previously granted to him.

There was again some

fighting between Gruffyd and the English in 1058, but in the main he remained

quiet until after the death of 2Elfgar about 1062. It seems he must have given

the English some trouble in the latter part of 1062, for Harold, (who in 1066

became the King of England), decided it seems, to attempt to crush this

dangerous and formidable enemy. He attacked the chief palace of Gruffyd at

Rhuddlan, near the end

![]() 1062; Gruffyd escaped by sea and Harold burned

the place, with the remaining ships.

1062; Gruffyd escaped by sea and Harold burned

the place, with the remaining ships.

This event had an

unfavorable effect upon Gruffyd's power and prestige, especially in South

Wales; and it is evident that he had many enemies among the Welsh, who regarded

him as an oppressor and tyrant.

Harold followed up his

first success and in conjunction with his brother Tostig planned a campaign by

both land and sea, Harold taking command of the fleet and Tostig of the land

forces, They began this vigorous campaign early in the summer of 1063. The

fleet left Bristol and sailed along the coast, landing at points where damage

could be inflicted. The English land forces gave up their armour and fought

much after the same fashion as the Welsh. No quarter was given and the

fighting, while of the guerilla kind, was desperate and furious. The Welsh

finally made a truce with Harold, and Gruffyd, it is stated by the chronicler,

was slain in August 1063 by Welshmen, because "of the war he waged with

Harold the Earl." It is alFo stated that the Welsh sentenced him to

deposition.

Harold had been ruthless

in his campaign against Gruffyd, but as soon as he had been disposed of he

procceeded to dispose of the kingdom, by dividing it between two native Princes

of Wales, who were half brothers of Gruffyd: (A 23) BLEDYN AB CYNFYN and (B 23)

RHIWALLON AB CYNFYN; however considerable portions, in the Vale of Clwyd, a

part of Radnorshire, and a portion of Gwent, became from this time English

possessions.

As stated, Gruffyd ab

Llewelyn ab Seisyllt, who was defeated and slain in Harold's campaign, was a

half brother of BLEDYN and RHIWALLON, who succeeded to his kingdom. Their

mother was ANGHARAD, daughter of MAREDYD AB OwAIN, (King of Wales) who first

married Llewelyn ab Seisyllt and later also married Cynfyn.

The Battle of Senlac, or

Hastings, in England, on Oct. 14, 1066, was an event of far reaching and

widespread importance to England, and through the great changes which were

wrought in the political and military affairs of England, by this decisive

victory of the Normans under William the Conqueror, over the English, its

results finally had great effect on the affairs of Wales. However, the Welsh

and those who trace their ancestry to Welsh families, have good reason to note

with pride, that while the Normans conquered England at almost a single stroke

![]() and practically by a

single battle, it took them two hundred and sixteen years to conquer Wales; and

it seems very likely they would not have succeeded even at the end of that long

stretch of years, covering as it did, nearly two and one-fourth centuries, had

they relied solely on military operations. The process finally adopted by the

Normans for the subjugation of Wales was, both military and economic. It

consisted of military campaigns of conquest, the building of strong castles for

the quartering of garrisons within the territory, and the permanent settlement

of their people on the lands adjacent to and protected by the castles ; also

the inter-marriages of some of the Norman leaders, with members of the princely

families of Wales, doubtless had some effect on the progress of events. There

were so many castles built by the Normans and their followers that Wales

finally became known as "the land of castles."

and practically by a

single battle, it took them two hundred and sixteen years to conquer Wales; and

it seems very likely they would not have succeeded even at the end of that long

stretch of years, covering as it did, nearly two and one-fourth centuries, had

they relied solely on military operations. The process finally adopted by the

Normans for the subjugation of Wales was, both military and economic. It

consisted of military campaigns of conquest, the building of strong castles for

the quartering of garrisons within the territory, and the permanent settlement

of their people on the lands adjacent to and protected by the castles ; also

the inter-marriages of some of the Norman leaders, with members of the princely

families of Wales, doubtless had some effect on the progress of events. There

were so many castles built by the Normans and their followers that Wales

finally became known as "the land of castles."

Harold, the English king

who fell at the battle of Hastings, was the

•

same Harold who bad

defeated Gruffyd ab Llewelyn, as we have seen,

in

1063, and the Welsh were probably, in general, pleased over his fall; however,

they found later that the Normans were no better friends than he.

Prior to the

"Norman conquest" Wales had remained as a whole almost intact, and

subject only, to the authority of the native kings and princes. It is true some

fragments of Mid-Wales (Powys), had been wrested away by the English or Saxons,

but in 1066 it was practically the same Wales, territorially and politically,

that RODERICK THE GREAT (Rhodri Mawr) ruled over in 844. During this long

interval there were several Welsh kings and princes who paid personal homage to

the Saxon or English Kings and acknowledged their political superiority, for

defensive purposes during the Danish incursions, and doubtless for other

reasons, growing out of the wars between the rulers of England and the rulers

of Wales; but at no time did these foreign kings have anything whatever to do

with the government of Wales, or with its affairs as a separate and independent

nation. Its independence as a nation had in no way been abridged, prior to

1066; except possibly by the victory of Harold over Gruffyd in 1063, and almost

immediately after that event Harold handed the territory and government over to

the native Welsh princes BLEDYN and RHIWALLON AB CYNFYN, with its independence

practically unimpaired. It is well to state here that perhaps, the methods

![]() of the Normans were as a whole, no greater

factor in the final overthrow of Welsh independence in 1282-1283, than the

internal strife between the princely families of Wales and their following.

of the Normans were as a whole, no greater

factor in the final overthrow of Welsh independence in 1282-1283, than the

internal strife between the princely families of Wales and their following.

Returning to the internal

affairs of Wales we find that BLEDYN and RHDVALLON, to whom Harold had

delivered the possessions of Gruffyd ab Llewelyn in 1063, combined with Eadric

the Wild, who possessed lands in Herefordshire and Shropshire, England, and

refused to submit to the new Norman King of England, "William the

Conqueror." The allies laid waste the English lands of Eadric in 1067,